Two striking scenarios take place in the Gulfton community:

In one, a 17-year-old Afghan refugee, driving a car owned by his family, finds himself chased by seven police officers for disobeying a traffic light whose colors he was never taught about. He was also never taught that the sirens of a police car mean you must stop or yield. He is arrested for violating traffic laws and running from the police, all of which he does not understand because he does not speak English. No effort is made to explain this system to him and he spends the night alone in a cell, unable to understand why he is being detained. He is released only after an English-speaking peer explains to the police that he is a refugee who was unable to attend drivers’ ed due to language barriers.

In one, a 17-year-old Afghan refugee, driving a car owned by his family, finds himself chased by seven police officers for disobeying a traffic light whose colors he was never taught about. He was also never taught that the sirens of a police car mean you must stop or yield. He is arrested for violating traffic laws and running from the police, all of which he does not understand because he does not speak English. No effort is made to explain this system to him and he spends the night alone in a cell, unable to understand why he is being detained. He is released only after an English-speaking peer explains to the police that he is a refugee who was unable to attend drivers’ ed due to language barriers.

In the other scenario, a 9-year-old comes to Houston from Guatemala, shy, distressed, and unable to speak English. Less than a year later, he finds himself engaging with friends, making stellar grades in school, and performing in a play he wrote.

While in wildly different scenarios at first glance, the two boys are in almost identical situations. They are both displaced into a system without the resources necessary to assimilate them properly into this new and daunting society.

The difference between the stories is the helping hand of the community.

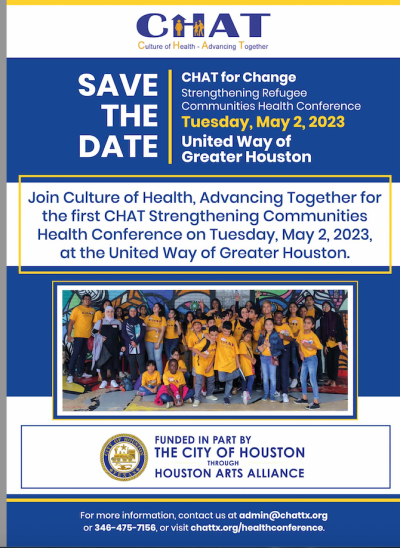

The success story of 9-year-old Hector’s acclimation into American society is among the many heartwarming examples of work by the Houston nonprofit organization Culture of Health, Advancing Together. The organization, known as CHAT, has been aiding refugees and immigrants through education programs here since its creation in 2015.

The orchestrator of this organization is Aisha Siddiqui, is the ultimate example of an accidental hero.

An immigrant from Pakistan, Siddiqui had her fair share of struggles acclimating to a new country with very little systemic help.

“I saw that even though I had an education, could speak English, and could drive, I would oftentimes still hit a wall and wonder why it was like that for me,” she said.

“I saw that even though I had an education, could speak English, and could drive, I would oftentimes still hit a wall and wonder why it was like that for me,” she said.

Siddiqui remembers moments of intense micro-aggression, and outright discrimination, toward her during her acclimation process, from being waved off by professors as inferior to being called unconscionable names at gas stations.

“At the same time, I saw immigrants around me in southwest Houston that I felt like were still standing out and not quite blending in or being properly enculturated,” she said. “And I thought, if I came across those things even when I can communicate with people, what must immigrants who are less prepared than me be experiencing?”

The question led Siddiqui to enroll in the University of Texas’ School of Public Health, where she went on to earn a doctorate degree.Through connections with faculty, experience within the community, and specialized research on how health affects an immigrant’s ability to enculturate into society, she realized her calling was greater than she had ever anticipated.

“At first, I was thinking about serving third-world countries, but then I realized that there is so much more I needed to do here in this community,” she recalled.

“So, I told my husband my heart is still in the community, so that’s where I want to work. I just wanted to help people, but I didn’t realize you had to have a platform to get started. I didn’t know what it took to start a nonprofit. I jumped into it without knowing how to swim.”

Throwing herself into the whirlwind of nonprofit creation proved challenging, but with the rallying force of her community, things started coming together. First, there was a website to worry about.

She put some feelers out on her Facebook page, asking friends if anyone knew how to create a website from scratch. A woman completely unknown to Siddiqui created a new website for free.

Then there was the issue of finding a place in which to operate.

“No one wanted to give space,” she said. “They said, ‘We don’t want to make this space a refugee camp.’ Space is a major issue because with many refugee communities, if you don’t do the programming where they are, they don’t come.”

After operating out of a building with no running water outside of a mosque, Siddiqui realized it was time for a change of scenery. Either through fate or a stroke of luck, CHAT was given a free three-bedroom apartment in which to run its services.

Lastly, who was going to do the work? While an outpouring of volunteer work from the community was greatly appreciated, the idea of building a paid staff loomed large.

For this, she needed to look no further than fellow community workers and students at the University of Houston’s Public Health Department. Through internship programs, partnerships and volunteers, Siddiqui was able to create an organization equipped to empower Houston’s immigrant and refugee population.

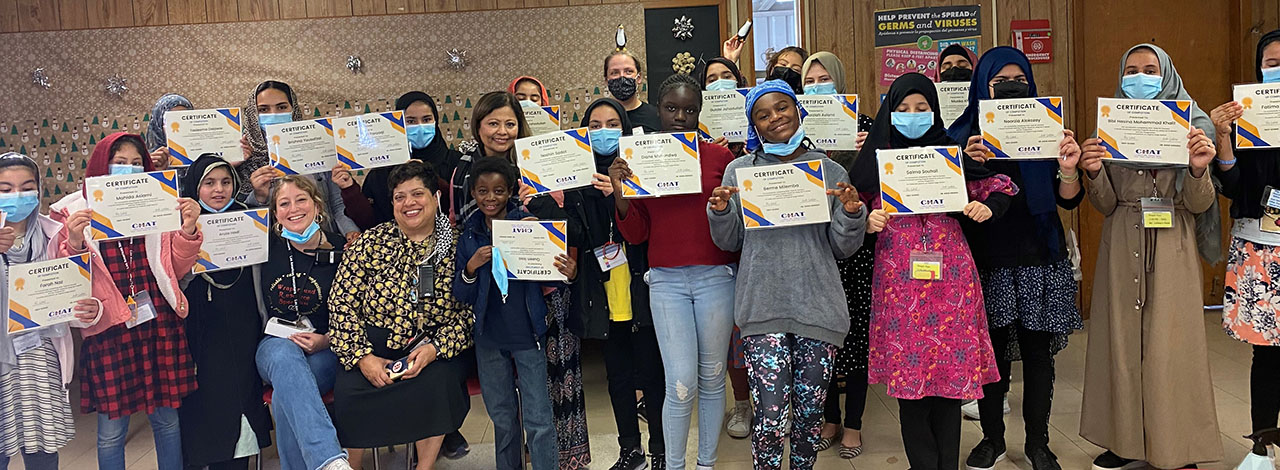

And empower it does, through programs targeted specifically toward children and students struggling through the acclimation process. Girls Club for Success, a program developed by a student volunteer, aims to support girls and young women in schools struggling through language and culture barriers.

“Often times schools would reach out and say that there is this girl that is just constantly crying and not speaking because there is a language barrier. That’s the most difficult thing to cross. The student often feels isolated because they cannot communicate. In addition, there is a lot of bullying that goes on.

“So our community helpers from the University of Houston, many of whom come from the same population and ethnic background, speak the student’s language.”

“So our community helpers from the University of Houston, many of whom come from the same population and ethnic background, speak the student’s language.”

Through support groups, one-on-one conversations, museum trips and lessons on health habits, CHAT has boosted the lives of many of these clients, allowing them to open up and unlock their potential.

In addition to programs that focus on education, health, language, and acclimation, CHAT puts a large emphasis on celebration of culture through the arts.

“Art is healing. It is an international language. It has no boundaries, so for people who cannot express themselves through words it is very important,” Siddiqui said.

CHAT demonstrated how far expression can go through the release of its book, Reflections from Refuge, which showcases artwork from immigrant and refugee children within CHAT Academy.

Most recently, CHAT brought its passion to the streets through the Gulfton Story Trail — a collection of murals throughout the Gulfton community reflecting poetry written by children in CHAT programs.

Where graffiti once littered the walls, beautiful artwork can now be seen outside of Braeburn Elementary School, Las Americas Newcomer School and Jane Long Academy.

“People in the Gulfton area will probably never be able to go to a museum or art gallery, so if we bring art to them, it changes the perception of the community. Students feel proud of their neighborhood.”

The fatal Texas freeze of February 2021 created new challenges for Afghan refugees. With the little resources they had, such as food vouchers, becoming unavailable due to electricity blackouts, many refugees experienced extreme hunger and malnutrition, she said.

While other Houston residents seemed to receive an influx of information during the freeze, some immigrants and refugees felt left in the dark in more ways than one.

Other nonprofit organizations in Houston work closely with — and with funding from — the federal government to resettle refugees here through a formal structure.

Nevertheless, Siddiqui sees problems with the welcome they receive from people at large.

“Refugees are kind of dumped,” Siddiqui said. “The things that CHAT tries to do with refugees should have been a standard program. In six months, they are supposed to learn English, get a job, and buy a car, which is impossible. And then they get lost in the system.”

“We want the community to take its own charge,” she continued. “We don’t want someone from outside to come in and do it. We want the community to be so empowered that it can make itself a great community.”

Like many refugees, CHAT is looking for a permanent Houston home.

“Our biggest goal right now is finding a permanent home where we can do our programming without the fear of having to move out,” Siddiqui said.

— by Caroline Cabe